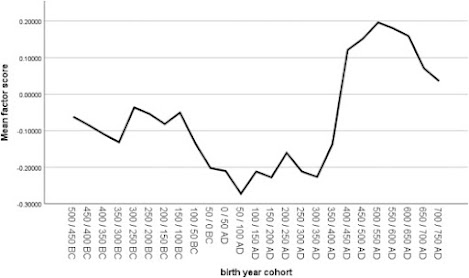

When I look at the historic photo of this group of five young passionate and enthusiastic scientists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) (1), I feel from their attitude the same eagerness and determination that I see in the eyes of my children who are around their same age today. In 1972, these five fellows truly expected that their report on “The Limits to Growth” would trigger a change in the development of humanity and motivate global leaders to act in protecting future generations. Their dream was cut short. Although the book became very popular around the planet with more than 30 millions readers, it was largely criticized by politicians and renown economists. The effort to bury this scientific work turned out to be so successful that the discredit lasted for more than thirty years. But the debate is still not over! In June 2022, we are celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Meadows Report, which is finally considered as the most influential environmental book and a major publication from the twentieth century. How did these young scientists go through this turmoil?

The tale started in 1968, with the intuition of an Italian industrialist, Aurelio Peccei, that the problems of humankind could not be solved individually, that there is an interrelation between different factors, and it is essential to apprehend their interactions. He looked for a scientific method to encompass all this complexity into one unique system and be able to propose possible evolutions for our societies.

He founded the Club of Rome to gather experts from different fields and investigate together this problematic. After a couple of years, the Volkswagen Foundation announced to the Club that they would no longer provide financial support because there was no clear methodology for this research and no positive outcome expected.

This is when the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) came into the picture. A team of scientists under the leadership of Dennis Meadows proposed to utilize a new computer-based simulations tool that was developed to analyze complex systems, establish correlations, and describe the evolution of time. This proposal from the MIT saved the Club of Rome and kicked off the study so anticipated by Peccei.

The team used the system dynamics to model the world’s economy and establish twelve prospective scenarios towards the end of the 21st century. The reference scenario was called “business-as-usual”, meaning that we don’t make any political intervention, we keep doing business in a free market, and continue the human expansion with no restrictions. In this scenario, the simulation showed major disruptions in the first half of the new century. The other eleven scenarios were contemplating the impact of extrapolations on several factors: resources, population, industrial output, pollution, and food production. To avoid the general collapse from the reference scenario, government interventions and controls were required, particularly on population (birth rate = death rate) and industrial capital stabilization (investment = depreciation). As you can see in the summary table below, the scenarios 10 & 11 reaching equilibrium would have required interventions in all the parameters, which was difficult to swallow for the proponents of the free market. Detailed explanations and graphs about each scenario can be read in the initial report and its following editions.

There are a few principles that are guiding these results. I will highlight only a couple of them that I appreciated very much.

First principle, the “Tragedy of the Commons”, from Garrett Hardin (1968). This is a very simple problem that we can experiment in our everyday life. It goes against the principles of the neoclassical economists who consider that the pursuit of our self-interest will lead to the maximum common good. Hardin said “No”, as it leads more to the destruction of the resource being exploited. He took as a model a community of shepherds: the common good is the land, a beautiful grassy meadow ideal for cows who are fans of grazing. Each farmer knows that he must take care of the land and not overuse it, but at the same time he is looking at his shepherd neighbor, who could easily be his best friend. Each one has an individual interest to make more money, and particularly more money than the other neighbor, because it is important to demonstrate who is the boss in the village. Then, a muted competition is engaged between the shepherds, with vibrant and victorious family debates on ambitious expansion plans during dinners in their respective home-sweet-home, followed by egoist dreams during the night in the bed, and false smiles between the men during the day on the field. Hypocrisy and pride spread out in the village while each farmer decides to put more cows on the land to be richer than his friend. And the story goes on like always until desperation hits. Eventually, self-interest destroys life and community, the parcel becomes arid and parched due to overuse, tears flow on family’s faces for the loss of the generous and nourishing land. Afterwards, we hear, in the streets and in the pubs, the whispering voices of the dwellers complaining about this shameful catastrophe, whereas these smarty-pants would have behaved identically or even worse in similar circumstances. This drama in the countryside repeats itself in the cities in the same manners. A corresponding tragedy is at the source of traffic jams which are generated by our self-interest to fight our own corner even if it jeopardizes the day for all of us.

Second principle, our difficulty to apprehend the effect of an exponential phenomenon. We are used to figuring out the impact of linear growth, so we have enough time to react and take appropriate countermeasures. However, we are completely blind towards the tsunami impact of an exponential growth. Out of the few examples taken in the Meadows report illustrating the dangerous consequences of this inability, I like the one of the lily pond (see below a nice explanation from artefacts.us website). Skeptical people will not believe the reality of a problem until they see it at scale, which is a devastating weakness in an exponential situation, because when the crisis becomes visible, it is already too late to react (here the last day of the month!).

Third principle, an important element of complexity that we have a hard time anticipating, is the feedback effect which can amplify or dampen any perturbation. The following example keeps us in the countryside (without the shepherds). It has several names, one of them being the “foxes and rabbits” model. It is extremely simplified and does not describe actual life, but it is very helpful in illustrating the meaning of feedbacks in complex system dynamics. The model shows that the population of rabbits and foxes is stabilized in the long run thanks to the interaction of positive and negative feedbacks, but the number of each population is never at equilibrium. It is always oscillating with sharp up and down which fairly represents the dynamic of complex systems. If there was no fox, the number of rabbits would go up exponentially, and if there was no rabbit, the number of fox would drop to zero due for starvation.

The "Limits to Growth" applies these principles to their system dynamics. For instance, the growth of the population is exponential with positive feedback loops (“the larger the population, the more babies will be born each year.”) which can be moderated through a negative feedback loop of deaths, depending on the rate of each one. This is the same for Industrial output with investment (capital added per year) as positive feedback loop, and depreciation (capital discarded per year) as the negative one.

I found some clear explanations about these principles, and others, in “The Limits of Growth Revisited” (2011) from Ugo Bardi. This book is particularly interesting because the author dedicates several chapters on how the Meadow’s report was perceived globally. This is the most comprehensive compilation of positive and, for the most part, negative evaluations. Effectively, after a few positive and constructive initial judgments, progressively the report gave birth to a large and uncontrollable outcry. Political and economist leaders lashed out on the report without any restraint. In order not to fall into an exasperated state, I will not relay here all the wretched comments that you can find in Ugo’s book, such as “a piece of irresponsible nonsense”, “lack of humility”, “garbage in, garbage out”, “a projection for disaster”, “starvation specter”, “the MIT Malthusians”, “doomsday data” ... Just one example to read is the article published in the New York Times on April 2nd 1972, from Peter Passels, Marc Roberts and Leonard Ross. The tone and the argumentation are a good example of the reaction from authorities and non-scientist representatives. One important input provided by economists, and not considered in the report, is about price, as a variable which will adjust the utilization of resources over time and reduce depletion impact.

Many of the denigrations were using mistaken statements and fallacious accusations. Some of the most common criticism utilized over and over by analysts were that the study wrongly estimated that some important mineral resources would run out before the end of the twentieth century or that the world would collapse around 2000! It is nowhere in the report, but all commentators passed around the same erroneous message without checking its relevancy.

One reason given is that politicians and economists could not stand that scientists give a voice on the governance of the world. It is out of their domain of responsibility; they are not legitimate. I guess it is overstated, but I got confused when hearing some of speeches from politicians. For instance, Ronald Reagan, one of the most virulent opponents to the report, who howled with the wolves, and stated in a public talk on January 21st, 1985: “We believed then and now, there are no limits to growth and human progress, when men and women are free to follow their dreams. And we were right.”

The Bell Jar had rung and the proposals from Meadow’s report ended up hidden in the back of the drawers of our general blindness. Growth became the creed of all politicians for several decades.

Fortunately, this is not the end of the tale.

In recent years, the indisputable recognition of the climate crisis gave to the report a new lease of life. Numerous studies have been published showing the accuracy of the trends estimated initially by the Meadows team (i.e., Matthew Simmons, Graham M. Turner, Charles A. S. Hall & John W. Day, Gaya Herrington...), and confirmed that ironically the basic scenario (Scenario 1 “Business-as-usual”) is aligned with current trends in all the key factors applied in the system dynamics model.

Even amongst the most vocal economical adversaries of the report, such as personalities like Robert Solow or Milton Friedman, one of them, William D. Nordhaus (Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences 2018), did a turnabout (see detailed review in Ugo Bardi’s book). In 1992, he recognized the importance of the report, but kept one criticism on the lack of importance given to the “technological progress” whose impact is considered only as delaying the inevitable collapse but could not help to avoid it. I recommend his conference in 2018 for the award ceremony of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, where he is proposing, amongst other actions, to apply price increase policies to fight against climate change.

I also found it interesting to see the growing legitimacy of the report through its subsequent editions in parallel to the increasing number of international conferences on environmental problems. Although the chairman of the first UN conference in Stockholm in 1972, Maurice Strong, was profoundly influenced by the Meadows report, nothing happened afterwards: zero international event between this first UN Conference and the Earth Summit in 1992. At this conference in Rio, George W. Bush, the successor of Ronald Reagan, was provocative in repeating the same politician message: “Twenty years ago, some spoke of the Limits to Growth, and today we realized that growth is the engine of change and the friend of the environment.” Challenging the economic growth was still considered as a sacrilege in that time. The UN Stockholm+50 conference taking place this June will tell us if we have been able to go beyond this hurdle.

Ugo Bardi and Carlos Alvarez Pereira led a new edition for the fiftieth anniversary titled: “Limits and Beyond - 50 years on from The Limits to Growth, what did we learn and what’s next?” that has be published just on time for the Stockholm+50 conference.

The intention of these young scientists was not to predict the future. More reasonably, they were expecting that, by warning the world about the risk of civilization collapse, their research would offer new perspectives, would provide valuable data to influential people, and encourage them to thereby take initiatives to modify the trends and build a bright future for next generations. They were convinced that their report would give the readers optimistic perspectives and reasons to believe that these planetary problems were totally manageable and could be solved with applicable solutions.

In fact, their recommendations from scenarios 10 & 11 at “Equilibrium” are everywhere in the news today: recycling to reduce our dependency on nonrenewable resources; better product design for durability and repair and less discarding because of obsolescence; adoption of less-polluting technologies, methods and materials; development of sustainable agriculture to avoid more soil erosion and pollution due to intensive food production; shift from maximizing manufacturing and sales of products to fostering human development with priority on education, health care, and cultural activities; Diverting capital to making food affordable for everyone...

So what happened to these young scientists? I have been interested to look at their individual personality, as if they were somewhat part of my family, I mean the family of those who are worried but persistent in seeking to build a livable place for the generations to come.

Donella Meadows

Donella Meadows is not the first one for being a woman, it would just be elegant but not fair. She is at the top because - we owe credit where credit’s due - she has been the lead author of the report and I believe that the impact and the quality of this publication would not have been this high without her writing and expressive talent.

From 1972 until her death in 2001 she taught in the Environmental Studies program at Dartmouth College. She was closely linked to the nascent ecologist movement and was communicating with her students about alternative non consumerists lives. This is outstanding and consistent with the conclusion of the report, but I would not be surprised that malicious people had utilized this overlapping to discredit her legitimacy. She seems to have been quite optimistic on the possibility to develop a democratic society that would provide equal wealth to all citizens.

To preserve the memory of this author, the Donella Meadows Institute (DMI) has set up a website collecting many documentations. It shows clearly how active Donella has remained during all of her life, continuing to teach, and write several books as well as more than 700 weekly articles called “The Global Citizen”.

In one of her letter, she talked about the dream house: “You can’t look at that perfect house without imagining the perfect family living inside. Big house equals happiness. They’ve been selling us that dream for decades.” The dream house size was increasing constantly after each decade, from 1200 square feet in the 1940s to more than 2000 sqft in the 1990s. Why? Donella has the answer: “Just for making us dissatisfied with what we’ve got.”

In one interview, Jorgen Randers made a beautiful tribute to Donella talking about “her warm heart and her faith in humanity. She is inherently wise and good to make positive things”.

One quote from Donella that I really love and would make it mine if I could: “The scarcest resource is not oil, metals, clean air, capital, labour, or technology. It is our willingness to listen to each other, and learn from each other, and to seek the truth rather than seek to be right.” We should pacify the relationships between scientists, economists, and politicians. There is no benefit for humanity to refuse cooperation, the truth is hidden in the interstices between the expertise of each discipline.

Dennis Meadows

Dennis Meadows is the former husband of Donella. He is recognized as the leader of the MIT scientific team who completed all the studies for the report. There were 16 members in total and their average age was around 26 years old. Dennis is still the most active representative of the team in medias and there are many interviews available online to listen to his views on our world today. He looks like someone who became stoic after a long-life experience and wants to enjoy his remaining days without expecting too much from his peers. He is proud to have developed games to help people understand how systems thinking (such as systems dynamics or mental models) work. I hope Dennis will not complain as I took the liberty to reproduce below a simple example of one of his games (Arms Crossed), just to give you an idea and maybe make you curious to learn more about these games.

He likes games because they are good tools to change the way that people think. Thanks to the experience, the players will think differently. It is far more efficient than just talking which is never good enough to convince someone. Nothing better than experimentation. Dennis is educating people living around him in the New Hampshire. He is really applying the principle of stoicism philosophy such as educating with practical exercises, trying to improve the world just within his community or having reasonable expectations.

He has a few other dearest arguments repeated in different instances, which I feel are very persuasive. Let me summarize some of them below:

He is not a fan of sustainable development and more in favor of what he calls “resilient development”. I think what he wants to say is that we will face so many environmental calamities in the future that we must be prepared to live in survival development mode to collectively overcome these difficulties.

His is very critical towards politicians and he would like scientists to be more present in the political field which is far too dominated by those who hold a legal background.

Dennis’ view on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) methodology is that they started first with what was politically acceptable and then tried to trace out scientific consequences, whereas the Meadows report was looking first at what was scientifically known to simulate afterwards political consequences. For instance, the population growth or the economic GDP levels are exogenous to IPCC study, although these factors have an enormous impact on climate change.

The global problems, such as climate change or pandemic, affect everyone, but they require global actions with only long-term benefits. So, if someone focuses their actions on these global issues, they will not see any results and will be discouraged. On the other hand, there are universal problems, such as water or air pollution, soil erosion, flooding, deforestation, which can be managed locally. Each one of us should focus on these issues, as we can solve them here and now, get quick return and be enthusiastic about it.

Jay W. Forrester

Jay was recognized as a key scientist in the development of the computer industry. He created a few inventions which were essential to the development of our digital world. Jay worked on computer simulations of the dynamic of complex systems and their interconnectivities. His first book, “Urban Dynamics” (1969), analyzed several urban development factors such as population, housing, and industry, and how their fluctuation would affect the development of a city. During a presentation of his results at a conference in Italy, he met Aurelio Peccei who invited him to a Club de Rome session to be organized in Bern in 1970.

Jay remembers this session as being on the verge of seeing the Club end. This was the day the Volkswagen Foundation decided to cut off funding: “We were very close to no project at all!”. In the afternoon, he convinced the participants to come to MIT and spend a couple of weeks to better understand his computing systems. Jay was so excited about this initiative that he spent the whole flight back from Rome to the US drafting a model of the world evolution following the method of system dynamics. He filled up so many pages that he used the empty seats around him to lay down the model which lengthened more than 8 meters eventually. It became the seed of the model to build all the scenarios of the “Limits to Growth” report.

Until he passed away in 2016, Jay remained an advocate of system dynamics and the complexity for humans to apprehend their evolution. The computer used for the Meadows report simulations is called World3 and it is still available to reproduce the scenarios, see Systemic Alternatives website here.

Jorgen Randers

Jorgen joined MIT to study a PhD in physics, but after just a few months he realized that it was not what he wanted to do. One day, he attended a talk from Jay on Urban dynamics. He went to him afterwards and simply said: “here I am, and I would like to work with you”. This is how that he got engaged in the team.

For ten years following the report’s publication, Jorgen kept trying to convince people with no success. Eventually he gave up. I believe that this failure is at the source of his pessimism. In 2012, he wrote his own book: “2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years”. He anticipated that we would face rising inequities, unemployment, poverty, extreme weather. For him, social collapse is more likely to happen than ecological collapse. His main recommendations are to shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy and particularly solar energy for which he is a strong supporter; to develop sustainable agriculture and decrease meat consumption; to support poor countries in reaching a higher development model; to establish more equity and make rich people contribute more financially; and to lower the global population.

He also poses a sensitive question about our governance: can we implement necessary long-term actions when our political programs are mainly driven by the short term? Can we impose constraints to our citizens who don’t want to reconsider their current standard of life? Overall, Jorgen seems to be the most disillusioned scientist of the Meadows team.

William W. Behrens III

The beginning for Bill is a bit similar to that of Jorgen. He was at MIT when he heard about the proposal to create a research team on system dynamics. He ran to Dennis’ office and said, “this is fascinating, I would like to be in the team”. Dennis replied that he was the first candidate, so he was in! Bill is the most discreet member. After the publication of the report, he followed Donella and Dennis to Dartmouth College, but after a few months he decided to change his way of living and retire from our consumerist society. He bought a wood house in a forest in Vermont, without electricity, telephone, with only bio agriculture and animals.

In 1995, he founded the renewable division of the Green store in Belfast, Maine. Then, after 2003, he co-founded companies to design and build solar panel for houses in all the New England region.

He looks like a very positive and humble person. It is just enough to look at the website of his company Revision Energy to see how passionate he and his team seem to be to work for the deployment of solar energy.

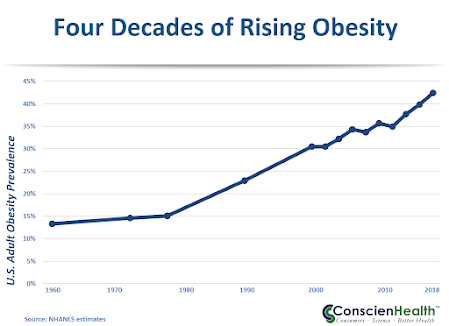

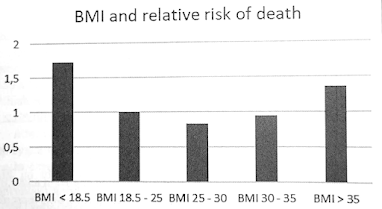

The Tale of Mobility

The automotive industry benefited greatly from the rapid growth of the world’s population since the 1970s. I could not find a graph showing the increasing volume of vehicles in operations in the world, so I estimated that the expansion went from around 100 million units in the middle of the last century to 1.7 billion today. The industry is expecting further increases in the next decades. An indicator exists to measure the number of vehicles per 1,000 habitants, which managers in the automotive sector use to justify investments in specific countries. For example, they will compare India at 44 vehicles per 1,000 habitants to USA at 816 and expect a huge potential for business development. We are in a vicious circle, because the expansion of vehicles in operation will require new roads infrastructure and will encourage further urbanism expansions.

However, there are social forces which are going in the opposite direction. For instance, Sophie Howe, the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, is behind the decision taken by the Welsh Government to scrap the proposal to build a motorway south of Newport that would have relieved the traffic on the main M4 highway. She justified this position by saying: “people in Wales are used to using their cars, even for short distances. Building new roads just perpetuates that old model. We’ve got to find a way of breaking that cycle.”

Citizens are also more active in condemning big projects which are either unnecessary or getting out of control with huge waste of both time and money. Many of these programs are in the mobility domain, such as rail, highways, bridges which are never finished, or even airports (Berlin Brandenburg Airport, Notre-Dame-des-Landes in France, the Castellón airport in Spain which has never been used and received the local nickname of the “first pedestrian airport in the world”!).

There is a weird term to nominate this kind of projects: “boondoggle”. Its origin is as fancy as the word itself: either from Tagalog, an Austronesian language commonly spoken in the Philippines, or from Ozark English, spoken by several Native American tribes, or from a 19th century American pioneer or even from a Roosevelt Troop of Boy Scouts! In any case, I would prefer us to concentrate our efforts on projects which are necessary, useful, and providential. Jorgen Randers proposed that society take the lead and regulate capitalism by allocating a portion of its resources to projects which are both profitable and beneficial for society. For instance, tax carbon on petrol vehicles to boost sustainable mobility investments, incentives on houses equipped with solar panels, or the expansion of local green hydrogen hubs (production and refueling stations).

But what kind of tale is this one? Is it the weak citizen “David” fighting against the strong “Goliath” corporation? Or is it another illustration of the tragedy of commons, where the rich, the poor, the master, and the servant, are all acting for their selfish interest using the common good just as an excuse for their confrontations? This trait of human personality should be carefully considered by the urban designers of our future smart cities. There will be so many common areas, such as public spaces, shared mobility, open offices, or multiples sensors, that it will be necessary to ensure a collective responsibility to avoid the deterioration of these premises.

The common areas will be protected only if they are respected by people who will care for them. We should feel guilty if we are not respectful with the commons. I know that it can be despicable to consider that respect is based on the fear (according to Albert Camus), but we cannot ignore it. I believe the same is happening today regarding our relationship with nature. In the past, the countryside and the backwoods were scary and adventurous, particularly during the night. This fear was giving us a sense of respect to the environment. The development of urbanism took us away from this emotion. We are missing something here. We should learn again this feeling of wonder and astonishment in front of the mystery of nature.

Arthur Rackham is an exceptional English illustrator of fantasy literature. His art reminds us of how much we were impressed and scared by the elements of the countryside. He takes us in a fairytale wonderland where nature is intensely wild, full of secrets and impenetrable depths. A marvelous collection of Rackham’s work is reproduced in this video with hundreds of illustrations.

The relation between nature and fantasy leads us to an intriguing case in the literary history. It is about Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s passion for spiritualism, to the point that towards the end of his life he gave credibility to a set of photos taken by young girls showing fairies and gnomes into the countryside. Conan Doyle believed there was something in nature beyond our normal reality, something supernatural. He said that if the existence of these fairies would be true, it would "mark an epoch in human thought". He was hoping that something unexpected could happen to transform our too much materialistic world. This affair, named the “Cottingley Fairies”, from the village where it happened in the 1920s, became a worldwide scandal with never-ending debates about the truth behind these images. We had to wait until the early 1980s for the two young girls, now old ladies, to confess that the photos were faked, that they were using cardboard cutouts of fairies. The creator of the famous detective, Sherlock Holmes, had been lured by passion at the end of his life! I have a tenderness for this writer. I respect him very much for his poetic aspiration and his faith in the mysteries of nature.

But, like the unexpected end of a ghost story, the two women ended up in disagreement. Yes, all the other photos were hoax, but not the last one! One of them claimed the last one was genuine, and the fairy was not fake! I leave it up to you to make your own judgement on that one, you can find the photo below. As a matter of fact, you might have already noticed this curious appearance. If you look closely at the header of this article, it seems that the fairy in the photo introduced herself into the life of the Meadows team, likely to give them power, confidence, and relief. This is the proof, if we ever needed one, that nature would always remain generous and magical.

(1) Actually, of the five, four were indeed young scientists, around 30 years old. But Jay Forrester, (second from left) was 54, and already professor at MIT