Dennis Meadows (left in the image) and Ugo Bardi in Berlin, 2016

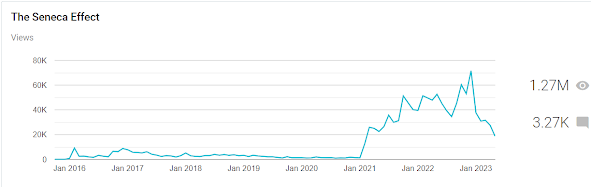

A few days ago, I received a message from Dennis Meadows, one of the authors of the 1972 study "The Limits to Growth," about a previous post of mine on "The Seneca Effect." I am publishing it here with his kind permission, together with my comments, and his comments on my comments. I am happy to report that after this exchange we are "99% in agreement."

Ugo,

I read with interest

you review of the Michaux/Ahmed debate.

Normally I greatly benefit from your writing. But in this case it seemed

to me that your text totally avoided addressing the central point -

replacing fossil fuels as an energy source with renewables will require

enormous amounts of metals and other resources which we have no

reasonable basis for assuming will be available. It is not true that

peak oil was presented principally as a prediction. Rather critics of

Hubert's original analysis misrepresented it as an effort to predict in

order to ridicule it - just as Bailey did for the

Limits to Growth

natural resource data from World3. I was struck that your critique

of Michaux did not contain a single piece of empirical data - the strong

point of his research. Rather you engaged in what I term "proof by

assertion."

I am personally convinced that there is absolutely no possibility

for renewables to be expanded sufficiently that they will support

current levels of material consumption. I attach the text of a memo I

recently wrote to other members of the Belcher group stating this

belief (*).

Best regards Dennis Meadows

_____________________

Dear Dennis,

first of all, it is always a pleasure to receive comments from you. It is not a problem to be in disagreement on some subjects -- the world would be boring if we all were! Besides, I think our disagreement is not so large once we understand certain assumptions.

Let me start by saying that I fully agree with your statement that "there is absolutely no possibility for renewables to be expanded sufficiently that they will support current levels of material consumption." Not only is it impossible, but even if it were, we would not want that!

So, what do we disagree about? It is about the direction to take. The

fork in the path leads in two different directions depending on the efficiency of renewable technologies: Path 1):

renewables are useless, and Path 2):

renewables are just what we need.

I strongly argue for Path 2) in the sense that we definitely do NOT need to "support current levels of material consumption" to create a sustainable and reasonably prosperous society. But let me explain what I mean by that.

First, in my opinion, the problem with Michaux's report is that it underestimates the efficiency of renewable technologies. He says that renewables are not really renewable, just "replaceable." He, like others who use this term, means that the plants that we are now building will not be replaceable once fossil fuels are gone. In this case, creating a renewable infrastructure will be a waste of resources and energy (Path 1).

This view may have been correct until a few years ago, but it is now obsolete. The recent scientific literature on the subject indicates that the efficiency of renewable technologies (expressed in terms of EROI, energy return on energy invested) is now significantly better than that of fossil fuels. Furthermore, it is large enough that the materials used can be recycled using renewable energy. There is a vast literature on this subject. On the specific question of the EROI, I suggest to you

this paper by Murphy et al. You can also find an extensive bibliography of the field in our recent paper, "

On the history and future of 100% renewable research."

Of course, not everything is easy to recycle, and a future renewable infrastructure will have to avoid the use of rare metals (such as platinum for fuel cells) or metals that are not rare, but not abundant enough for the task (such as copper, that will have to be largely replaced by aluminum). That is possible: the current generation of wind and PV plants is mostly based on abundant and recyclable materials. Doing even better is part of the natural evolution of technology. What we can't recycle, we won't use.

There is a much more fundamental point in this discussion. It is the very concept that we need renewables to be able to "replace fossil fuels," in the sense of matching in quantitative terms the energy produced today (in some views, even exceeding it in order to "keep the economy growing"). This is impossible, as we all agree. The point is that

renewables will greatly reduce the need for energy and materials to keep a complex civilization working. If you think, for instance, of how inefficient and wasteful our fossil-based transportation system is, you see that by switching to electric transportation and shared vehicles, we can have the same services for a much smaller consumption of resources. This concept has been expressed by Tony Seba in a form that I interpret as,

"Renewables are not a cleaner caterpillar-- they are a new butterfly"

That doesn't mean that the geological limits of the transition aren't to be taken into account; the butterfly cannot fly higher than a certain height. Then, it may well be that we won't be able to move to renewables fast enough to avoid a societal, or even ecosystemic, crash. On this point, please take a look

at a paper that I co-authored, where we used the term

"the sower's strategy" to indicate that the transition is possible, but it will need hard work, as the peasants of old knew. But staying with fossil fuels is leading us to disaster (as you correctly say in the document for the Balaton group) while moving to nuclear fission simply means exchanging a fossil fuel (hydrocarbons) for another fossil fuel (uranium). Going renewables is a fighting chance, but I believe it is the only chance we have.

There is an even more fundamental point that goes beyond a certain technology being more efficient than another. Going renewables, as

Nafeez Ahmed correctly points out, is a switch from a predatory economy to a bioeconomy. Our industrial sphere should imitate the biosphere that has been using minerals from the Earth's crust on land for the past 350 million years (at least) and never ran out of anything. As I said elsewhere, we need to do what the biosphere does, that is:

1. Use only minerals that are abundant.

2. Use them sparingly and efficiently.

3. Recycle ferociously.

If we can do that, we have a unique opportunity in the history of humankind. It means we can build a society that does not destroy everything in order to satisfy human greed. Can we do it? As always, reality will be the ultimate judge.

Ugo

__________________________________________________________________

The answer from Dennis Meadows

Ugo,

Thank you for sending me your article. I agree that the main

difference of opinion lies in the direction to take. I am reminded of

the defining characteristic of professors - two people who agree on 99%

and spend all their time focusing on and debating the other one percent.

Because I largely agree with you, my only relevant comment on what you

say is that you have overly limited our options:

So, what do we disagree about? It is about the direction to take. The fork in the path leads in two different directions depending on the efficiency of renewable technologies: Path 1): renewables are useless, and Path 2): renewables are just what we need.

I would not choose either path;

rather I believe it is time to quit focusing on fossil energy scarcity

as a source of our problems and start concentrating on fragility. The

debate -renewables versus fossil - is a distraction from considering the

important options for increasing the resilience of society.

Dennis Meadows

___________________________________________

A minor point. You say, "It is not true that peak oil was presented principally as a prediction." I beg to differ. I have been a member of ASPO (the Association for the Study of Peak Oil) almost from inception and part of its scientific committee as long as the association existed. And I can say that one of the problems of the approach of peak oilers was a certain obsession with the date of the peak. That doesn't disqualify a group of people whom I still think included some of the best minds on this planet during that period. The problem was that few of them were experts in modeling, and models are like weapons: you need to know the rules before you try to use them. By the way, you and your colleagues didn't make this mistake in your "Limits to Growth" in 1972; correctly, you were always careful of presenting a fan of scenarios, not a prediction. Later on, Bailey and his ilk accused you of having done what you didn't do: "wrong predictions." But that was politics, another story.

_____________________________________________________

(*) Statements about being realistic about technology, alternative energy, and sustainability

Dennis Meadows

April 11, 2023 message to the Balaton Group

Dear Colleagues,

I have often described politics as the art of choosing which of several impossible outcomes you most prefer. It is important to envision good outcomes. It may be useful to strive for them. But it is important to be realistic. The recent discussion about technology, alternative energy, and sustainability are based on several implicit assumptions, which I believe are unrealistic. At the risk of being an old grump, and recognizing my own limited vision, I list here some statements that I believe from the study of science, history, and human nature to be realistic.

#1: There is no possibility that the so-called renewable energy sources will permit the elimination of fossil fuels and sustain current levels of economic activity and material well- being. The scramble for access to declining energy sources is likely to produce violence.

#2: The planet will not sustain anywhere close to 9 billion people at living standards close to their aspirations (or our views about what is fair).

#3: Sustainable development is about how you travel, not where you are going.

#4: The privileged will not willingly sacrifice their own advantages to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor (witness the US.) They will lose their advantages, but unwillingly.

#5: The rapidly approaching climate chaos will erode society's capacity for constructive action before it prompts it.

#6: Expansion and efficiency are taken as unquestioned goals for society. They need to be replaced by sufficiency and resilience.

#7: History does not unfold in a smooth, linear, gradual process. Big, drastic discontinuities lie ahead - soon.

#8: When a group of people believe they must choose between options that offer more order or those affording greater liberty, they will always opt for order.

Unfortunately so, since it will have grave implications for the evolution of society’s governance systems. Dictators will always promise less chaos than Democrats.